In a new serialized novella from Hugo Award-winning author Sarah Gailey, a fractured group of undesirables work together to nurture and nourish each other while navigating a dangerous world that would just as soon see them dead. Still—inch by inch, meal by meal—they build their own future. Have you eaten?

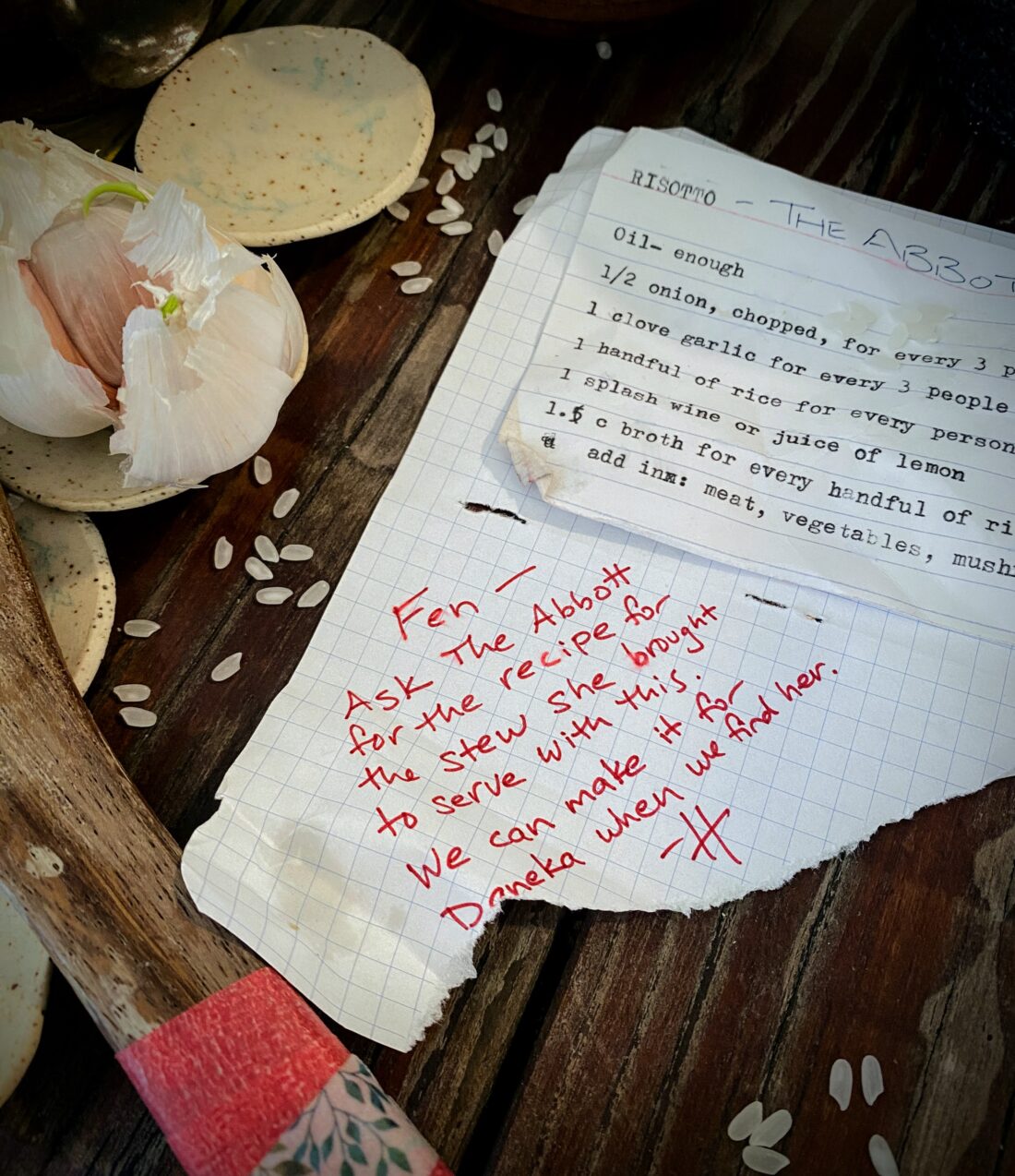

The Abbott’s Risotto

Oil—enough

½ onion, chopped, for every 3 people eating

1 clove garlic for every 3 people eating

1 handful of rice for every person eating *rinse once

1 splash wine or juice of 1 lemon

1½ cups broth for every handful of rice

Add in: Meat, vegetables, mushrooms

- Heat oil. Soften & brown onions and garlic.

- Add oil. Add rice, stir until edges go clear.

- Add wine, stir until liquid is gone.

- Add a little broth. Stir until liquid is gone. Repeat until all broth is gone.

- Add whatever you like.

Harper walks behind everyone else as they make their way down East Wacker Drive in what used to be the Loop. The four of them are in the center of the street, not trying to hide their approach. Not looking to make anyone nervous, Morrow had said when they entered the city. Not looking to make anyone pissed, Quan had replied.

Harper hadn’t said anything. They don’t say anything now either. They just hang back, half a block behind everyone else, hood up, raising a hand in acknowledgment whenever Fen glances nervously over her shoulder at them. Fen’s still worried that Harper’s going to disappear, leave the group, strike off on their own. It’s an understandable worry, but Harper wishes Fen would just sit with that worry for half a day instead of constantly bleeding it out onto every surface she touches.

The blacktop is still cracked from the time a tank rolled through the neighborhood. Harper looks down at the zagging splits in the street, remembers the sound of treads. The road here wasn’t made to support that kind of weight, but nobody cared then and nobody’s left here to care now. Harper didn’t even care, not at the time, even though they loved these roads. It was hard to care about anything but the ten minutes that had just happened and the ten minutes that were on the way. Still, that tank should have fallen through the asphalt, through Lower Wacker, down onto the now-submerged Riverwalk. Should have cracked the pavement straight through.

The other three are loud up ahead. Loud on purpose—that’s what they all agreed on. No sneaking, no surprises. Treat the Rosemary Patch like a bear den, that’s the smart approach so it’s what they’re doing. Quan and Fen are bickering, an are-we-there-yet back-and-forth that has a smile in it on both sides. Morrow’s got their hands deep in their pockets, just listening, but their bigness is loud and for once they’re not trying to hide it.

The buildings that line one side of the street get a little taller. They’re almost to Stetson Avenue now. Harper looks up into the empty eye sockets where rows of glass windows used to be. The piercing whistles of lookouts echo up the block, twee-twee-twee-twee. Fen’s chin snaps up at the sound.

Harper sighs and runs a palm across the patchwork stubble on their scalp. “Here we go.”

The group’s strategy of being obvious pays dividends. As they approach the remains of Columbus Plaza, four figures melt out of the shadowy mouth of one of the buildings. Nobody Harper recognizes—they’re kids, practically, all wearing red rags around their biceps, all making faces to make it clear that they know how to kick ass. They’re skinny but in a growing-too-fast way, not in a starving way, and they all have all their hair. Harper figures there’s probably a good number of adults standing just out of sight, letting these cubs get some experience. It’s a promising sign.

“Stop there,” one of the kids yells, a scrawny Black kid with a tight fade and a missing front tooth. The kid’s got a scowl that would stop a tank in its tracks.

“No problem,” Fen calls. She holds her hands out at her sides. Quan and Morrow do the same. Harper’s instructions echo through everyone’s mind: Everyone stay relaxed. Don’t look tense. If you’re calm, they’re calm.

One of the other kids—tall, white, weedy, blonde hair that’s falling into her eyes—has a big stick that she bonks against the blacktop. It’s genuinely a little menacing. “What are you doing here?”

“We’re looking for the Rosemary Patch,” Morrow says. They’re doing the worst job of looking calm. They’re thinking about what’ll happen if these kids decide they want a fight. Dreading the possibility of combat with children. The tension radiates off them in sick shivers.

The scrawny kid with the fade looks behind him, back into the building he came out of. The blonde shoves him and hisses something that sounds like “Don’t look, dipshit.”

“It ain’t here.” This from the smallest of the kids, who wears a ball cap that’s too big for his head. “You’re in the wrong place. Turn around.”

Fen takes a slow step forward, her hands still out at her sides. “I think it is here, actually. We’re here to see, um.” She hesitates long enough that Harper takes half a step forward, but then she sticks the landing. “We’re here to see The Abbott.”

The kids lose their composure immediately. They’re grabbing each other and talking over each other, gesturing at the same building the one kid had looked into. After a few seconds of this, an adult figure strides out of the shadows with the loping impatience of a chaperone who needs to impose order.

Harper’s eyes track the well-muscled neck, the broad bony shoulders, the long swinging arms. They tug their hood down over their eyes just a little further.

“Fuck’s sake. Everyone downstairs, we’re going over security protocols again in the morning. And Devon? Don’t let me hear you calling anyone else a dipshit.”

The blonde kid crosses her arms. “What if he’s being a dipshit?”

Fen interrupts. “Sorry, I didn’t catch your name.”

“You can call me PJ. Because that’s my name.”

Harper bites their lips to keep from smiling, mutters to themself, “That stupid fucking joke.”

Fen holds out a hand to shake. “PJ, I’m Fen.” The wind is catching on the hollowed-out buildings, making the street loud. The two of them talk, trading introductions and explanations and code words. PJ leans around Fen to get a look at Harper but doesn’t seem to recognize them.

“Alright,” PJ says in a voice loud enough to carry up the block. “Come on down.”

She leads their group across the old six-lane street, toward the river. Fen hangs back, waiting for Harper to catch up.

“Looks like we’re in business,” she says. Her eyes are sparking with anxiety.

“Looks like. You scared of heights?”

Fen cocks her head. “Not really. Why?”

Harper lifts their chin toward the railing on the edge of the street. Fen watches as PJ, the four kids, Quan and Morrow approach. PJ crouches down and adjusts something at Devon’s waist.

And then Devon dives over the edge of the overpass.

Fen doesn’t make a sound. Her eyes go hard and sharp. She looks from PJ to Morrow to Quan to Harper, her nostrils flaring, her breath still.

Harper holds up a hand like they’re trying to steady a spooking horse. “It’s okay. Nothing’s happening. That’s just how we get to where we’re going.”

Fen gives a little shiver, rolls her shoulders. “I don’t like this.”

“You just don’t like surprises,” Harper says. “But you’re gonna like this. I promise. Unless you’re scared of heights, and then you might never speak to me again.”

When Fen peers over the edge of the overpass, she isn’t scared by the drop from Wacker to Lower Wacker. “And you’re sure it’s safe?”

“When have I ever lied to you?”

“Never. But . . . you also haven’t said that it’s safe, so I don’t think you’d count it as a lie, would you?”

Harper grins. “Well. You won’t die, anyway.” While PJ is clipping the rest of the kids to their lines and sending them down, Harper tells her about the hidden street beneath Lower Wacker where the Rosemary Patch used to be located. “You’re not going that far, though. There’s an old service tunnel that goes from Lower Wacker into the old auto pound. You’ll be walking a few blocks to get there. Don’t worry. PJ will get you there.”

Fen leans far over the railing to look down at the street below. “How come we didn’t just go straight there? Why do we have to go underneath everything?”

“Chicago used to be monitored by drones. One hundred percent of the time,” Harper says. “These days, who knows. Better not to risk leading anyone to home base.”

Morrow gives a joyful shout as they slip over the edge of the railing, a loose length of cord in their hands. Quan goes soon after, silent and trembling with nerves. Fen gives Harper a small, loose salute, then turns toward PJ.

“My turn?”

PJ gives her a warm smile. “You’ll do great.”

“Where do I clip in?”

“You don’t,” PJ replies. “The kids wear harnesses. We don’t have enough for adults.”

“Is it safe?”

“If you don’t want to take the line down, you can walk”—she points into the distance—“that way, until you come to the part of Wacker that collapsed onto Lower. It makes a kind of ramp down. It looks dangerous, but the kids play on it all the time, so you’ll probably be safe to scramble down.”

Fen frowns. “What made it collapse?”

“Tank. This street’s not made to support that kind of weight.”

Harper jolts. “When did they come through again?”

They’re still far enough away, their face still shadowed enough by their hood, that when PJ gives them a curious glance, she doesn’t recognize them. Still, Harper is thankful when Fen recovers PJ’s full attention by asking about how to hold the line without tearing up her palms. Harper stays quiet after that, waiting for Fen to drop over the edge before stepping forward.

PJ peers at them, her eyes searching. “Sorry, I didn’t catch your name. Fen said you were with her group, but— Hang on.” Her face hardens and before Harper can dodge, PJ’s hand has darted out to snatch their hood away. “You,” she breathes.

Harper gives her a wary smile. “Hey babe.”

PJ’s arm twitches like she wants to slap Harper across the mouth, but no blow comes, which is how Harper knows she hasn’t forgiven them yet. “The fuck are you doing here?” She bites out the words like a cold wind.

“I’m with Fen and them. Traveling together. We’re looking for—”

“For Daneka, right. Fen said. So. You and Fen are together.”

“Not—” Harper sighs. They’d somehow forgotten PJ’s weapons-grade jealousy. “Just traveling together. Nothing else. Will you let me go down so we can see The Abbott? The others are waiting for me down there.”

PJ shakes her head. “Fuck no. Nobody down there wants to see you.”

Harper rocks back on their heels. “Hey now,” they murmur.

After a moment, PJ twists her neck, rolls her eyes, drops the anger from between her molars. “Sorry. That was mean and it’s not true. But, Harp—you can’t just come rolling back in after what you did. You left without saying goodbye to anyone. You hurt a lot of people. You have to know that.”

“I know. And I’m prepared to talk to The Abbott about it.” Harper reaches out and touches PJ’s upper arm, lets their fingers drift down to her elbow. They don’t acknowledge the fact that the “lot of people” they hurt included PJ. Was probably mostly PJ. “Trust me. I can handle myself on this one.”

“You can handle yourself on anything,” PJ grumbles. And then she gives a sharp tug on the line that’s knotted around the handrail. When it holds strong, she gives it to Harper. “You better not leave without saying goodbye this time. I mean it. I’ll kick your ass.”

Harper loops the end of the line around each of their thighs, then grip the slack in both hands. They swing one leg over the rail, then lean back to kiss PJ on the cheek. “Thanks, babe.”

Before they can so much as grin at her, PJ plants her palms on their shoulders and gives them a hard shove. Harper tumbles off the edge of the overpass with a long-buried whoop of freedom.

When their feet touch the asphalt of Lower Wacker, the others are already standing in a cluster nearby, talking softly. Harper approaches, grinning, ready to rib Quan for his nerves—but when they get close, the group parts, and Harper’s grin falls away.

The Abbott is here. She’s as short as the scrawny kids who’d been standing guard, as broad as a barrel, and as old as the city itself. She aims her dark, creased face up at Harper and measures them with a cool, steady gaze.

“So. You’re back.”

Quan looks up at Morrow, openly perplexed. “Back? Harper’s from—”

“Here,” Harper interrupts. “I’m from here. And yeah, Abbott, I’m back. Me and some friends, who I see you’ve already met.”

PJ drops to the pavement behind Harper. “We gotta move,” she says. “We’ve all been here too long already. Abbott, I thought you were going to wait for us at the Patch?”

“A little mouse told me I’d want to come see the visitors for myself,” The Abbott says. She reaches out a hand and, without looking, rests it on the head of the kid in the too-large baseball cap. “He never met you while you were here, Harper, but he still knew you on sight. You’re something of a scary story among the children.”

PJ steps forward, pinching the bridge of her nose with one hand. “Please. We seriously have to go. Can you and Harper talk on the way there?”

Harper flinches—when they lived here, that would have earned anyone a sharp rebuke from The Abbott, but it doesn’t come. The Abbott simply nods. “Thank you for keeping us on time. Lead the way. Harper, you’ll keep me company in the back of the group. I walk slower these days anyway.”

The Abbott waits while PJ herds the group toward the service tunnel. She stands still until Harper sighs and holds out an arm. “You need someone to lean on?”

“I don’t need it, but I’ll take it anyway,” The Abbott says. She loops her arm through Harper’s and pats them on the forearm like they’re a sturdy horse. “I’ve missed you.”

“You haven’t.”

“I have!” The Abbott lets out a raspy laugh. “Now, tell me why you’re back. I heard it from your friends, but I want to hear it from you.”

Harper explains. They tell her about Daneka, about her disappearance and the messages they’ve been getting from someone who seems to be Daneka but isn’t. They fill her in about Peter, then about Peter and Morrow getting together and falling apart, then about their little group’s journey across the border from Wisconsin into Illinois. They tell her about Fen, who relies on them almost as much as they rely on her.

“This Bouchard,” The Abbott says thoughtfully. “Who you stayed with in Wisconsin. Is he part of our family?”

Harper thinks for a moment. “Don’t know. But his wife—I think you’d like her. I convinced her to convince him to get back to work by telling her how much the state cops would hate it if a bunch of queers made it into Illinois. She laughed so hard I thought she was gonna choke.”

“So you’re hoping to see Daneka here.”

“Fen is. Personally, I think it’s too much of a long shot. But—”

The Abbott clicks her tongue. “You’re a pessimist. I don’t know why. You were raised better than that.” Then she purses her lips and whistles once, high and sharp. The group ahead stops and waits until Harper and The Abbott have caught up to them. “Alright, children,” she says, addressing the new arrivals more than the actual kids. “In a minute, we’re going to arrive at the Patch. Our visitors are going to earn the right to stay with us by making dinner. Enough for all ten of us.”

Fen glances at Harper with obvious surprise. Harper shakes their head and shrugs. Neither of them offered this to The Abbott—she’s simply setting her terms.

“Excuse me,” Quan asks, his voice as careful as it gets. “How long can we stay?”

The Abbott grins. “That’ll depend on how much I like dinner, won’t it?”

She leads them into the Rosemary Patch, and Quan, Fen, and Morrow gawk at the sheer scale of the underground community that sprawls throughout the old impound garage. Sturdy little houses line the walls, built out of the shed skin of the city: old street signs, sheets of corrugated metal, tiles pried up from the lobbies of abandoned skyscrapers. Clusters of adults sit out in the common area, processing food or studying playing cards or watching the children who chase each other across the building. The air is a little sharp with the smell of old motor oil and too-close bodies, but overpowering those smells is the smoke of cookfires and the unmistakable aroma of baking bread.

PJ jogs forward and leans close to Harper, murmuring in their ear. “You haven’t been here since the bakery started up. The new moms run it. Fresh babies and fresh loaves. Bet you wish you never left.”

Fen hears and interrupts, and Harper can’t decide whether to be irritated or relieved. “Harper, you used to live here?”

“We talked about this already,” Quan says. Fen gives him an irritated frown and he spreads his palms. “It’s not my fault you were too busy flirting with PJ to listen. Harper’s from here.”

“I don’t want to get into it,” Harper says. “Peej, can you show us where we’re cooking tonight?”

PJ leads them to a small communal kitchen between two of the makeshift houses. It’s open, looking out into the common area, covered by a low overhang. Plywood is propped up on cinderblocks to form a U-shaped countertop, and bins below that counter hold plates and dented pots. Along the back wall, staples fill bins made of thick plastic with heavy screw-on lids: flour, rice, onions, cassava.

PJ points to a corner with a hotplate. Underneath it is a row of water jugs and a basin of assorted cooking implements. “This is the only spot that’s available. Everywhere else is reserved for the night. You should have gotten here earlier if you wanted a better setup.”

Morrow peers into the basin. “These are all broken. Look,” they add, holding up a wooden cooking spoon that’s held together in the center with duct tape. “What happened here?”

“Probably Jaan, practicing their drumming,” she says. Then she adds, “That’s my kid. They love music.” She doesn’t look at Harper when she says it, and the not-looking is as loud as the words themselves.

“It’s fine. We can cook with broken stuff,” Harper says. “Thanks for showing us.”

PJ nods. “No problem. Just hand me your packs and I’ll get out of your hair.”

Quan balks. “Our packs?”

“I’m going to search your shit,” PJ replies lightly. “Don’t worry. You’ll get everything back.”

Quan grips the straps of his backpack with white knuckles. “I don’t want—”

“You don’t want to argue on this one,” Harper murmurs to him.

“The fuck I don’t,” Quan insists. “What’s she looking for?”

PJ gives Quan a carnivorous grin. “I don’t know, Quan. Trackers. Guns. Palmsets with fake videos of my friends, maybe.”

Quan’s mouth opens, then snaps shut as he looks at Morrow. “You told her?”

“I told the Abbott,” Harper interjects.

“There hasn’t been time for The Abbott to—”

Harper laughs. “Never assume she hasn’t done whatever she might take a mind to do, Quan. Trust me on that one.”

“Okay, but we aren’t the ones who made the videos of Daneka,” Morrow points out.

PJ raises her eyebrows. “Then you shouldn’t need to worry about what I’ll find in your bags. I’ll plug your palmsets in, too. You must be carrying a bunch of dead batteries by now.”

The four of them hand over their packs—Quan reluctant, Morrow and Fen resigned, Harper almost relieved. PJ thumbs the empty carabiner that hangs from Harper’s backpack strap. “No keys?”

“Nowhere to save keys for,” Harper says. “You have a kid?”

PJ can’t restrain a small, soft smile. “Yeah. They kick ass. Too smart for their own good, and they’re a little thief too. They remind me a lot of you. You’ll like them. If you want to meet them, I mean.”

It takes Harper a moment to find breath, and then another moment to find words. “Yeah. Yeah, I’d like that.”

And then PJ is gone, and The Abbott is gone, and the kids who’d been standing guard are gone, and it’s just the four of them, alone again in a strange kitchen.

Fen steps in close to Harper. “Do you want me to handle making dinner? I don’t mind.”

Harper shakes their head. “You don’t know how to do this.”

Quan looks up from where he’s rummaging through the broken cooking implements. “What? Of course she does. And she has the recipe box.”

Harper turns to Fen. They take a deep breath and fold their arms across their chest, and in that moment, it’s as if no time at all has passed since they left the squat. The light that falls through the street-level grate above dapples Harper’s shoulders, and the muggy river air hangs around the two of them like the falling wings of dusk, and Harper is just as irritated with Fen as they were on the path behind the houses in the neighborhood where they became family to each other.

“You’re gonna make me say this?”

Fen visibly braces herself. “Yes. Unless there’s something you think you can’t say to me.”

“Fine. You don’t have a recipe in your box that can handle this situation, Fen. You aren’t prepared here. Every recipe you know how to cook calls for eggs or butter or meat.”

Morrow speaks up. “Not the—”

“Don’t say not the vegan ones. Those are worse. You think we’re getting handed chia seeds down here? Applesauce? Corn? The point is, we’re not cooking with the kind of resources you’re used to.”

“But if everyone works together, we can figure out—”

“Everyone’s not going to work together, Morrow,” Harper cuts in. “Not with us.”

Fen looks around at the vast expanse of the underground garage. It’s filled with the hum of life. “They seriously don’t have any of that stuff down here? Eggs, I mean? For all these people?”

Harper laughs. “I’m not saying they don’t have it. They probably do. But they’re not going to give us any of it to cook with. Do you understand? They’re not going to give us the things that make it easy to make something tasty. We’re being tested right now. And that’s why you’re not cut out to make this dinner.”

Fen bristles. “Because, what, I can’t cook when it’s tough? I didn’t see you complaining when—”

“No,” Harper interrupts. “Stop. You’re not hearing me.” They step close and put their hands on Fen’s shoulders, try to make their face kind and their voice kinder. “You can’t do this because you’ve only ever cooked for people who like you, Fen. People who will work with you to help you do a good job for them. And this isn’t that situation. You’ll hate how it feels to make dinner for people who are hoping you’ll fuck it up. It’ll hurt your heart. So let me do it this time, okay? I’m good at this.”

Fen blinks hard. “I didn’t know you knew how to cook,” she says softly.

Harper pulls her into a tight, brief hug. “You never asked.”

Fen joins Morrow and Quan beneath the lip of the overhang, and the three watch as Harper takes stock of what’s in the kitchen. It’s not much—the staples that are available to everyone in the community are foundational. “How the hell am I gonna turn this into dinner?” they mutter to themself.

Fen clears her throat. “Can we help?”

Harper shakes their head. “I know what I want to make. I just have to figure out how to make it into something worth eating. The Abbott’s probably told everyone not to help us, even if we can trade for ingredients.”

They turn to see a knot of young children, none of them older than eight, staring at Morrow. One of them breaks bravely loose from his friends and approaches the communal kitchen. He stands a couple of feet away and waits for Morrow to notice him. Finally, he just starts talking. “Hey excuse me I’m sorry but are you a giant?”

Morrow turns, laughing. It’s a freer noise than they’ve made in a long time. “Yes,” they reply, “I am a giant! A giant monster!” On the last word, Morrow holds their hands high overhead, growls, and trots toward the kids, who run away shrieking in open delight.

A game crystallizes effortlessly, the way games so often do with children that age. The children retreat and then, once Morrow’s back is turned, they race forward again. Morrow lets them get a little closer each time before turning around and letting out a roar, giving the kids an opportunity to flee. Fen is half collapsed with laughter; Quan rolls his eyes, but he can’t hide a small smile.

Harper smiles too, because they’ve found the solution to their problem. “Hey, Morrow.”

“I think you mean hey monster,” Morrow replies, grinning so hugely that they’re almost unrecognizable.

“Sure. Monster. Can you send the kids on a mission?”

Morrow flips the game effortlessly. The kids are thrilled to be given jobs—by a giant, no less—and vanish into the Rosemary Patch with absolute determination. While they’re gone, Harper rummages around in the bins. They pull out three good onions and a wrinkled half-head of garlic, and take mercy on Fen by asking her to dice them up. They measure out rice with their hands—ten big handfuls for ten people, plus an extra two handfuls just in case. They use a jug of water to give the rice a single rinse, dumping the starchy rinsewater into a big jar, which they’ll give to The Abbott since she likes using rice water to wash her face. She’ll think they forgot, and they’ll show her they didn’t, and the fact of their remembering will be a better gift than the rice water, they think. They hope.

Then they fill a huge pot with clean water and set it on the hotplate, bringing it to a boil, hoping something will appear that they can put into it.

By the time the water is bubbling, two of the kids are back. One of them—an Asian kid with two stubby pigtails—has bulging trouser pockets. “I got it,” they gasp.

“What’d you get?” Morrow asks, squatting down low to look the kid in the eyes.

They pull out two fistfuls of what looks like shards of tree bark. “Mushrooms!”

Morrow cups their hands for the kid to dump their prize into. “. . . Are you sure these are mushrooms?”

“Yeah! My mom dries ’em. They smell.” The kid points, wrinkling his nose.

Morrow sniffs the dark brown pile of mushrooms before mirroring the kid’s expression. “Those sure are mushrooms,” they agree. “Harp, can you use these?”

“These are perfect,” Harper says, leaning across the plywood counter to take the mushrooms. As they drop them into the boiling water, they call over their shoulder. “Thanks, kid. What’s your name?”

“Jaan!”

Harper doesn’t turn around until they hear the sound of small feet running away. Then, hoping Jaan is gone, they cautiously glance over their shoulder to see Morrow deep in serious conversation with the other child who’d come with Jaan. He looks like a miniature version of the kid with the fade who’d stopped them up on the street, and he’s got something small cupped in his palm.

“You’re sure it’s okay with your dad if we use this?” Morrow asks softly.

The kid shakes his head. “But he won’t know I took it. He has a big jar and this is only a few of them.”

Morrow nods and points the kid toward Harper. The kid approaches and reveals his offering: five, fragrant, salt-crusted preserved anchovies.

“Holy shit,” Harper breathes. “Thank you. This is—wow.”

The kid looks up at Harper with wide, shy eyes. “Can I see your head? I heard it got burned off when you left.”

Harper crouches down to take the fish, and bends their neck to show the kid the scars that map their scalp. “It was the year before I left, actually. When the old Rosemary Patch got raided and burned down.”

The kid reaches up to touch the scars without asking, and Harper flinches, both at the sudden touch and at the knowledge that their head is going to smell like fish for days. But they don’t move away. They let the kid feel the history of the Rosemary Patch that’s etched into their skin.

“Did it hurt?” the kid asks.

“Like hell. But it was worth it to help people. It usually is. You know, the way you helped us today,” Harper says.

The kid snatches his hand back. “I gotta go.” He runs off.

“You overplayed it,” Quan drawls. “Too didactic.”

“Where’d you learn didactic?” Harper retorts.

Fen pushes a sheet pan of chopped onions and garlic across the plywood. “Anything else I can help with?”

Harper shakes their head and drops the salted anchovies into the steaming water along with the mushrooms. They stir, waiting for the flesh of the fish to melt. “Unless you can find some oil.”

“I thought nobody here was going to give us anything,” Fen says, more than a bit tartly.

“They’re not giving us anything. Not voluntarily,” Harper replies. “The kids are stealing for us.”

Fen balks. “What? We can’t steal from these people, we’re their guests—”

“See? This is why I said you wouldn’t be able to make this dinner. You’re their guest, so you can’t steal from them. It’s different for me. I’m from here. I can be awful.” Harper gives her a look that they know makes them look like The Abbott. “Morrow, any other little thieves coming back to us?”

Morrow lifts their chin at a tiny figure that’s weaving through the common area, clutching a jar. “Looks like one more.”

The kid is as small and round as an apricot. She races up and nearly smacks into Morrow headlong before pressing the jar into their hands. “If anyone asks, I didn’t do it,” she says breathlessly before disappearing, her tiny head bobbing with every step she takes as she races away into the depths of the garage.

Morrow holds the jar up to their eyes and squints. “I . . . don’t know what this is,” they say slowly.

Quan bends to peer into the jar. “Nope. No clue.”

Fen plucks it from Morrow’s hand and holds it up to the thin light that streams through the holes in the garage roof. “The label just says ‘candle.’”

“No fucking way.” Harper snatches the jar away from Fen. “Fen, I’m so sorry. I was an asshole to you earlier and I was wrong.”

“What?”

Harper opens the jar and takes a deep sniff of the contents. “This is beef tallow. It’s fat. I can cook with this. I shouldn’t have yelled at you about needing butter because the relief I feel in this moment is enormous.”

Quan puts his hands on his hips and cocks his head to one side. “This is the most I’ve ever heard Harper talk.”

Harper gives Quan the finger and turns to the hotplate. They move the steaming cooking pot, which smells fishy and pungent from the anchovies and the mushrooms, to the side, and replace it with a different, wider-mouthed pot. They use a cracked wooden spoon to scoop a little beef tallow into the pot and wait for it to melt down. When it’s hot, they drop in the onions and garlic. After a few minutes the kitchen area is alive with the smell of ingredients becoming food.

The Abbott comes by to look in on Harper’s progress. Her eyes move from the jar to the steaming pot of broth. “Mmmm. I see.”

“Not taking notes at this time,” Harper says. “If you want to criticize, you’ll have to pick up a spoon and start cooking.”

The Abbott purses her lips in what might be either a reproach or a smile. Before she moves off, she presses a hand to Morrow’s arm and leans in close to them. “You and I should talk more. I’ve been hearing a lot about you from the children. Have you ever considered . . .”

Her voice fades out of hearing as she tugs Morrow off a ways giving them her pitch for whatever it is she wants them to do. Harper stirs the onions and garlic. They’re soft now, and just starting to brown, and Harper whispers the next steps to themself. “More fat, then the rice, stir until it changes.” They drop another scoop of beef tallow into the pot, let it melt, pour in the rice. They stir the rice over the heat, watching for the moment it becomes translucent at the edges. “Hey, Fen? Can you find me a ladle that will actually hold water?”

Fen ducks under the plywood and starts rummaging through the bin of kitchen implements. She holds up three different ladles, one of which is inexplicably slotted. The other two are badly cracked. Desperate, she pulls other bins out from under the counter and opens them. She clangs pots and pans together in her haste as she digs beneath them, hoping to find a dropped ladle.

“What the hell? Hey—hey, Harper!” She jolts up behind Harper with a bottle in her hand. “I found booze. Do you want some?”

Harper rounds on her with the piping hot irritation they reserve for moments when they’re interrupted mid-task. “Do I want? Some booze? Are you fucking—”

Fen raises an eyebrow. “For your recipe,” she says coolly. “Thought it might come in handy. But what do I know about cooking?”

Harper drops their cracked wooden spoon into the pot and clasp Fen by the shoulders. They press their forehead against hers briefly, then kiss her on the cheek. “I’m awful. Thank you, yes, I want this.” They take the bottle from her and open it, give it a smell, and grimace. “Not booze. Vinegar. Still useful, though. Thank you, I love you, go find me a ladle.”

Fen continues searching as Harper eyes the rice. It’s turning translucent at the edges. “Wine,” they whisper to themself, “then broth.” They eye the vinegar. It’s a deep golden color—it was wine once, they figure. They splash a little into the pot, then a little more, and that’s when Fen pops up next to them with a ladle.

They grab it with the hand that isn’t stirring. It has a perfectly intact bowl—but only two inches of handle remain. “This is basically a mug,” they mutter, but it’ll have to do, and they use it to scoop some broth into the rice just in time.

“So,” Fen says as Harper stirs. “Seems like this place is really home for you.”

“Mm.”

Quan leans almost all the way across the plywood. “Seems like you’re. You know. From here.”

“Mmm.”

Morrow comes walking back up, their arms spread wide, children dangling from each one. The Abbott is nowhere in sight. “Yeah, hey, so, you used to live at the Patch. Seems like you might want to tell us some stuff about that?”

“No,” Harper replies. “I want to finish making dinner.”

Fen touches the back of Harper’s heel with the toe of her boot. “What still needs doing? Can I help?”

Steam rises up from the pot, billowing around their face. “No. I’m just going to add broth and then stir until the rice soaks it up, then do that same thing again. And again, and again. And again. Until it’s done.” They let out a laugh that isn’t a laugh, not really. It’s more like a sigh with a stutter in it. “Suits this place.”

Morrow shakes off one of the children. The kid falls with a thump and a bright laugh. “Why?”

“Because that’s what it’s like living here. You just do the thing that needs doing, over and over, until you die.”

The Abbott approaches again, from across the common space. Her steps are slow and stately, perhaps a little stiff. Her eyes are locked on Harper, but she stops next to Fen. “I’ve made a decision,” she says. “I’m not going to wait until after dinner to discuss Daneka with you.”

“What? You never change your mind,” Harper says distractedly, ladling more broth into the pot.

The Abbott nods. “I’m changing it this time. Because I think you all will want make your plans tonight, rather than tomorrow.”

This catches Harper’s full attention. “Tonight? No, we need a place to sleep, please—Grand-Mère, you can’t—”

“Stop. And listen,” The Abbott says, in the voice of someone who is used to teaching children and adults how to behave. “I said you will want to make your plans tonight. You’re making me dinner, Harper, I’m not putting you out before dawn.”

Quan snorts. “Might want to taste the dinner before you decide.”

“Come over here and say that,” Harper offers.

“PJ went through your bags and didn’t find anything unexpected,” The Abbott says. “So I’m going to give you what Daneka gave me, so you can go and find her tomorrow.”

The air inside the Rosemary Patch goes still and silent. Harper drops the ladle and it strikes the floor with the clang of some enormous, dark bell. Morrow lifts their hands to the back of their neck and laces their fingers together, looking at the ground in an unconscious echo of the way Peter had tried to protect himself from their fists. Quan looks at Fen with wide, worried eyes. Fen covers her mouth with both hands, then says, “What?”

From an inside pocket of her coat, The Abbott produces two envelopes. “She was here two weeks ago,” she says. “She said you left her a note on a recipe card, saying to come here. I don’t know how she found us, but she did.”

“We talked about it for years,” Fen whispers. “We thought you were a myth, but—but we talked about coming here, trying to find you.”

“She did. But she said she was being followed. That’s why I didn’t send you all away when you told me about Peter—he’s already on his way. Bounty hunter, supposedly. Probably started tracking you all the way back at that house you were squatting in. PJ will handle him when he arrives. Thank you for doing him a bad turn, Morrow. I know you wish you hadn’t, but I’m glad someone did.”

Morrow doesn’t move, doesn’t speak. Behind Harper, the rice is beginning to sizzle.

Fen sways on her feet. “So Daneka’s not here. I— She’s not here? But she’s alive?”

The Abbott nods. “As of the time I last saw her, she’s alive, yes. She moved on three days after she got here. But she left these in my care.” She holds up one envelope, then lowers it to the countertop. “That one is for all of you. And this one,” she says, holding up the second envelope, “is just for you, Fen. She said you’d come. She thought everyone would probably come with you, but she said that if they didn’t, you still would. She cares for you a great deal, you know?”

Fen swallows hard, glances at Quan briefly before taking the envelope. “Thank you,” she whispers.

Harper takes a halting step toward the first envelope. Then they stop, turn around, swear down at the pot on the stove. They grab the ladle off the floor, add two quick scoops of broth to the pot, and stir hard and fast, scraping up the rice that’s browned on the bottom of the pot. “Fuck fuck fuck,” they whisper.

“Don’t worry about it so much,” The Abbott says. “All you have to do is keep going, and you’ll get there.”

Harper doesn’t acknowledge her. They just keep stirring. They know she was talking about the risotto, which she taught Harper to make when they were as young as the little thieves they’d employed to gather ingredients. They also know that she was talking about Daneka. And about coming home, and about growing up, and about everything else they’ve ever done and will ever do.

“This shit is why I left,” they growl. “Advice. Envelopes. Burnt fucking rice.”

Fen comes back around the counter and looks over their shoulder. “It’s not burnt. It’s just fond.”

“What?” Harper snaps.

“It’s just fond. The stuff that sticks to the bottom of the pot and turns brown. It’s fond. That’s where all the flavor is.”

Harper keeps stirring. “We’d better hope it’s a good flavor.”

“It will be,” Fen says, walking away, wanting to give Harper the space she knows they need to go through whatever it is they’re going through. Fen’s never come home to anywhere before. She doesn’t know what it’s like. But it looks like it hurts, and she knows Harper doesn’t like to be seen when they’re hurting.

Still. She pauses, touches the envelope that’s meant for the whole group. “You don’t have to come with me and Quan when we go find her. I don’t expect you to, I mean. I don’t think Morrow is coming,” she adds, looking over her shoulder at the place where Morrow and The Abbott are deep into another quiet, serious conversation. “I think they’re going to stay, probably. It’s okay if you want to stay too.”

Harper pauses in their stirring, which has become too frenetic anyway, too intense. They wipe their forehead on their wrist and look at Fen, really look at her, and their face is an open wound. They’re a cracked ladle, and all the love and pain and exhaustion in them is leaking out, and they can’t stand for it to splash onto Fen but there’s no way to keep that from happening right now so they let it happen. “You don’t sound scared.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean. Normally, when you ask me if I’m staying or going, you sound scared.”

Fen nods. She’s looking down at the risotto, which is nearly done, so that she doesn’t have to look at Harper. “The thing is. I figure it’s probably okay either way. You left this place, and then you came back, and it’s obvious that it’s still home for you. Even if you don’t want to talk about it—”

“I don’t mind talking about it with you. If you want to know, I’ll tell you.” They tip the big pot over the smaller one, pouring the last of the broth into the risotto along with the plump, rehydrated mushrooms.

“Either way,” Fen says firmly. “If you and Morrow decide to stay here, and I go off with Quan to find Daneka, that doesn’t mean we’ll never see you two again. It doesn’t mean you’ll forget about us. About me,” she amends. “I trust you not to forget about me.”

“And you’ve figured out that you don’t need me. Right? No, don’t—it’s not a bad thing,” they say before Fen can protest. “I just mean that for a long time, back at the squat, you didn’t trust yourself. You thought you needed me for backup. Right? And now,” they continue, not waiting for her to agree, “you know that you can do things on your own. So you’re not as scared of what’ll happen if I’m not there.” They turn off the heat and give the risotto a final stir.

Fen has her arms folded tight across her chest. “I don’t just want you around because I’m scared. Is that what you think?”

Harper taps the spoon against the edge of the pot. “I don’t think that’s the only reason you’ve wanted me around in the past. But I think it was in the mix. And now, I think you want me around because you want me around.”

Fen nods. “You really haven’t made your decision, have you? I’ve never seen you take this long to figure out what you want.”

Harper lets out a low, dry laugh. It’s a laugh that Fen’s never heard before. She thinks it might be their realest laugh. “Fen. You’ve been watching me try to figure out what I want since the day we met. You just didn’t know until now what I was trying to decide on.”

A group of children are gathering on the other side of the common area. The four guards, and the three thieves, and a handful of others. Fen points to them. “I think your risotto is going to have to feed more mouths than we thought.”

“You still don’t know? What choice I’ve been making?”

Fen shakes her head.

Harper eyes the growing mass of children. Jaan is near the front. “The way I see it, I’ve been looking at two options. There’s eating dinner with you and Quan and Morrow and Daneka, or there’s everything else in the world.”

“And you picked us?”

“Every time.”

The two of them stand side by side. Fen watches the children. Harper watches the risotto. They don’t look at each other, and they don’t touch each other, and they don’t speak. Their hearts beat at the same speed. They feel it together—the pain and fear and hunger of the months they’ve shared, the emptiness of the years that came before they knew each other, the echoing expanse of the future and all the hell that might be in it. Harper inhales, and a moment later Fen exhales, and neither of them has ever been so unalone.

Harper breaks the silence first. “This risotto’s gonna get cold fast. Not that the kids’ll care, but still. It deserves to be eaten hot.”

Fen nods. “Sounds good. I’ll go find bowls.”

Harper’s Risotto

Serves 10

18 cups water

4 tbsp beef tallow, divided into two parts

3 onions, chopped

6 cloves garlic

12 handfuls of rice *rinse once

2 splashes vinegar

1 cup dried mushrooms

5 salt-cured anchovies

Add mushrooms, anchovies, and water into the big pot. Boil until mushrooms are reconstituted and anchovies have more or less melted away.

- Heat tallow. Soften & brown onions and garlic.

- Add oil. Add rice, stir until edges go clear.

- Add vinegar, stir until liquid is gone.

- Add a little broth. Stir until liquid is gone. Repeat until all broth is gone.

- Add whatever you like.

“Have You Eaten?” copyright © 2024 by Sarah Gailey

Art copyright © 2024 by Shing Yin Khor

Photography copyright © 2024 by Sarah Gailey